Occupational cancer

2026 January 18

It’s been understood through the aviation community for years that we’re a bit different where a few health issues are concerned. Male military pilots, have statistically slightly more daughters than men in general. Considering aircrew in general, cancers are on average 1.50-2.0 times as likely in pilots, and about 1.5 times as likely in cabin crew. This is despite aircrew actually being fitter and healthier on average. We have to, after-all, have regular occupational medicals and meet minimum standards, than the background population. Mostly, we also actively following healthy lifestyles so that we can stay in the jobs we love. So, the biasing factors are probably even worse than the statistics suggest.

Of course, we’re far from unique in aviation. The first person to note that some professions showed greater incidences of cancer was an Italian, Bernardino Ramazzini, who around 1700 published a book showing that certain jobs, including dyers and chemical workers, miners, metal smelters and gas workers showed increased risk of cancer. He didn’t however come up with any theories as to why.

The first explanation of a specific causal relationship between occupation and cancer were made about two hundred and fifty years ago by an English surgeon called Sir Percivall Pott. He noticed that there was a significantly higher rate of scrotal cancer (or in the English of the time, “canker of the privities”) in chimney sweeps, and showed a connection between that and exposure to soot. Of course, in the callousness of that time, whilst nobody particularly disputed his conclusions, and a number of laws were enacted very quickly requiring better hygiene standards in chimney sweeps and *raising* the minimum age of British chimney sweeps to eight, in reality most of those were ignored. It took about a century before protection of British chimney sweeps from soot actually started to happen, and cancer rates dropped. In the USA I believe it was at-least as bad, not least as there chimney sweeps were mainly enslaved boys - for whom clearly workplace health and safety was something that happened to other people.

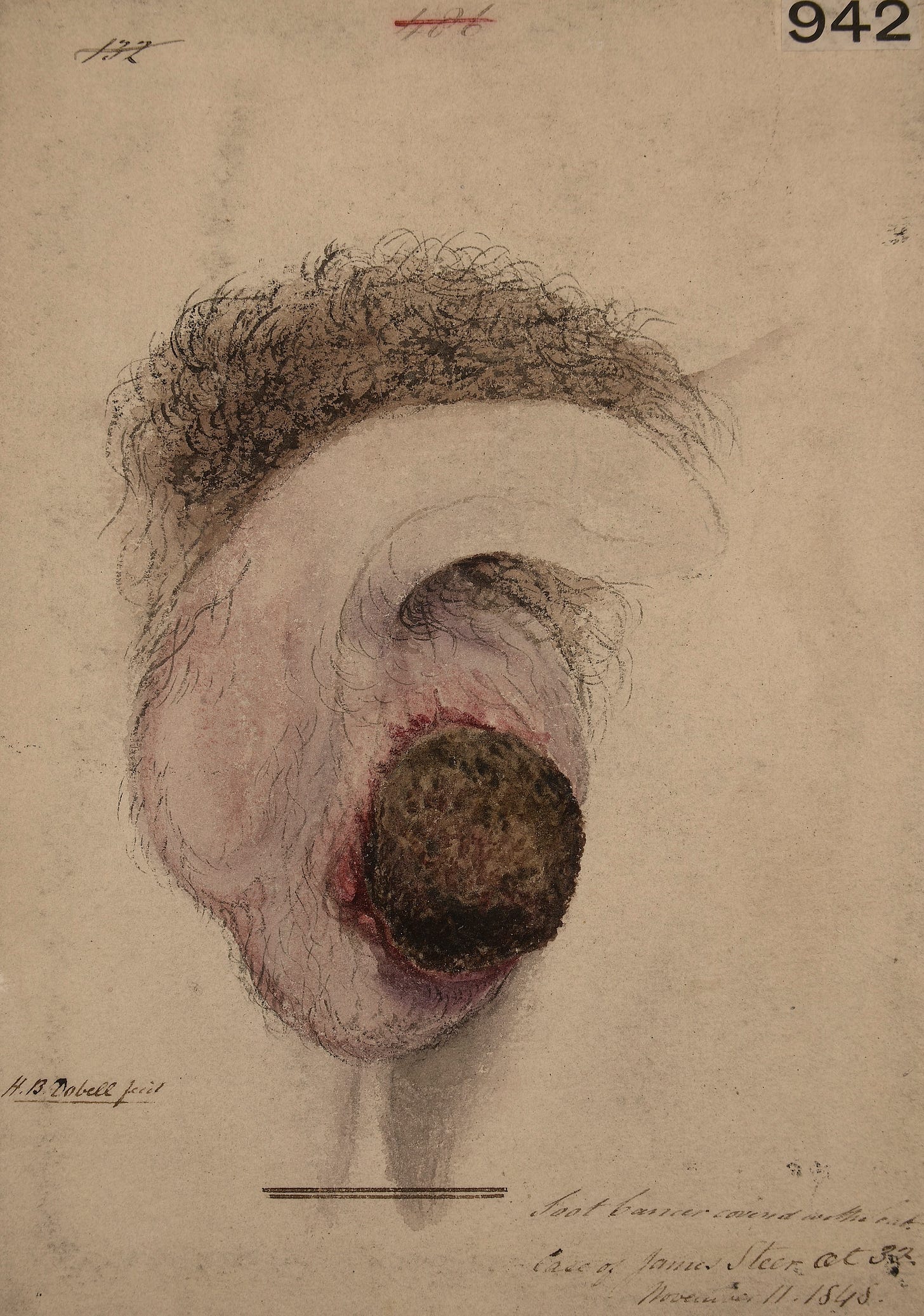

(Watercolour of chimney sweep’s cancer tumour, by Horace Henge Dobell.)

Various other links were made over the intervening years, but a massive breakthrough was made by two Japanese scientists, Katsusaburo Yamagiwa and Koichi Ichikawa, who published a paper in 1915 showing experimental work where they’d caused cancer in rabbits by exposing them to coal tar.

That all led to a whole raft of work, and our present understanding that by creating a toxic environment in a part of the body, what happens is that deformed cells are prevented from being instructed to self destruct by surrounding cells, and as a result they thrive when healthy cells may not. This has included understanding of the effects of asbestos, or coal dust, and even tobacco.

So we’ve learned some fundamental principles over the last 250 years. If you can identify the carcinogen, and eliminate it from the workplace, then you should be able to minimise the risk of cancer.

But, if only it were that simple. Back in the 18th century, Potts’ discovery of the mechanism of a link between scrotal cancer and soot exposure still took a century for real change to happen. That was basically because the people with the real power - employers and politicians, didn’t really want to do more than make token efforts. So how are we doing now on aircrew cancers?

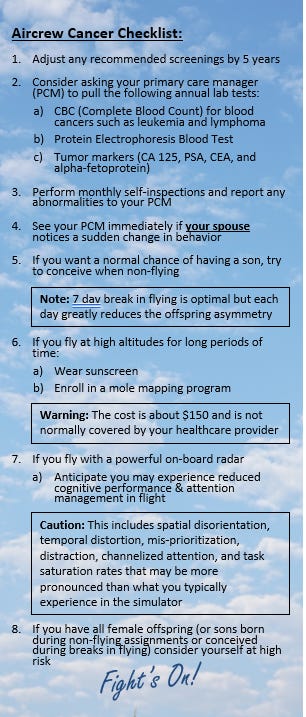

The truth is, not as well as we should. It’s true that regular medical screening and generally motivated people with access to good healthcare support, means that actually mortality due to cancer is little different in aircrew and the background population. But, eliminating the radiation, which most people assume is causing that cancer, is much harder. We can’t help that aeroplanes fly well above the ground, nor that combat aircraft and airliners alike have big radars in the front creating ionizing radiation. Adding extensive radiation shielding would make aeroplanes problematically heavy. Probably the best that we can do is to limit duty hours, and to enhance medical screening - which unfortunately we haven’t generally done. There is a military oriented charity in the USA, Aces and Eights, who I have mentioned before, who are doing something - but in the rest of the world, not a lot.

(Aces and eights aircrew cancer checklist.)

There’s another characteristic of aircrew is that we all love to fly, it may well be our sole or primary income, and thus we’re actively dissuaded by the professional environment from reporting symptoms or getting tested. Speaking from personal experience, that was definitely a significant concern for me, although I’m glad to say that commonsense and benign marital pressure did make sure that I got tested.

Whatever occupation you’re in, it is worth knowing what the carcinogens are in your workplace, and doing your best to avoid them. Sometimes it’s easy - painters and mechanics can wear protective gloves, people in dusty environments can wear masks, anybody getting close to chemicals can use barriers and regularly launder clothes (those poor chimney sweeps back in the 1800s were probably going to bed at night not only in the same clothes they’d been sweeping chimneys in, but under blankets they’d been using to gather up soot!).

Being personal about this for a minute - do I believe that my own cancer was potentially caused by my being a pilot? No, actually I don’t - the statistical evidence is that prostate cancer isn’t one of the ones that’s more likely in aircrew. Also whilst I’ve a fair number of flying hours (for the record, two thousand four hundred and twenty eight hours and twenty one minutes, plus whatever passenger flying I’ve done over the years), the vast majority of that was under 5,000ft and in aeroplanes without a radar. Frankly, I just got unlucky - but that doesn’t mean that I don’t now think that aircrew cancer is a very big deal, and I, and my colleagues, should take this very seriously. So should you, whatever your own professional environment.

Is lead protection in the form of PPE possible? Consider thyroid collars used in operating theatres. I'm not being in the least bit facetious as I suggest lead-line underwear. There is a lot to understanding of radiation including internal scatter and I know a little due to requesting x-rays but I'm not a radiologist.